RATING: ★★★★

I can’t decide whether I’m more interested in designing habit forming products or in finding out how to prevent products from forming my habits. Either way, Nir Eyal’s book, Hooked, is a fascinating read. It walks you through the steps that lead to forming new habits around a product using loads of real life examples and also offering a way to approach the inevitable moral questions. What follows is a subjective summary of the book with its key takeaways and some of my own thoughts attached. (Emphasis is from me.)

Introduction

In the introduction, we get a useful definition of habits:

“automatic behaviors triggered by situational cues”: things we do with little or no conscious thought.”

And a clue why companies employ this tactic in the first place:

“Companies that form strong user habits enjoy several benefits to their bottom line. These companies attach their product to internal triggers. As a result, users show up without any external prompting.”

Perhaps a not so surprising, but nevertheless extremely important fact:

“The convergence of access, data, and speed is making the world a more habit-forming place.”

A question comes to mind and before searching your own mind, you search Google. You feel a tad bored, lonely or frustrated and you go to one of the many social media outlets for some instant gratification. These are the internal triggers the author talks about.

Then we get a quick overview of the Hook model, which “describes an experience designed to connect the user’s problem to a solution frequently enough to form a habit”:

Trigger

- the actuator of a behaviour

- external or internal

Action

- the behaviour done in anticipation of the reward

- two things make the action more likely

- ease of doing it

- motivation to do it

Variable Reward

- “Feedback loops are all around us, but predictable ones don’t create desire.”

- The variable quality of a reward makes us come back and want more of the thing

Investment

- “The investment phase increases the odds that the user will make another pass through the Hook cycle in the future.”

- “The investment occurs when the user puts something into the product or service such as time, data, effort, social capital, or money.”

- “…the investment implies an action that improves the service for the next go-around”

“…this book teaches innovators how to build products to help people do the things they already want to do but, for lack of a solution, don’t do.”

1. The Habit Zone

This chapter starts with some more details of why habits are good for companies.

Increasing Customer Lifetime Value

“Fostering consumer habits is an effective way to increase the value of a company by driving higher customer lifetime value (CLTV): the amount of money made from a customer before that person switches to a competitor, stops using the product, or dies. User habits increase how long and how frequently customers use a product, resulting in higher CLTV”

Providing Pricing Flexibility

“You can determine the strength of a business over time by the amount of agony they go through in raising prices.” – Warren Buffet

When is the best time to hit your users with offering a paid version of something they’ve been using for free? Apparently not before they developed a habit of using it so that having to give it up would be a bigger pain than coughing up the price you’re asking.

“…after the first month, only 0.5 percent of users paid for the service; however, this rate gradually increased. By month thirty-three, 11 percent of users had started paying. At month forty-two, a remarkable 26 percent of customers were paying for something they had previously used for free.”

That’s not surprising if you know that it refers to evernote, a web app that makes collecting, storing, organizing and referencing pieces of content easy.

Supercharging Growth

Building a product with viral potential is a good start, but designing one with a short Viral Cycle Time (time it takes a user to invite another user) can make all the difference.

“For example, after 20 days with a cycle time of two days, you will have 20,470 users,” “But if you halved that cycle time to one day, you would have over 20 million users!”

That’s why products that become part of people’s everyday lives can spread through the entire population like wildfire.

Sharpening the Competitive Edge

“User habits are a competitive advantage. Products that change customer routines are less susceptible to attacks from other companies.”

Here, the author makes the point that habit forming products are a worthwhile business strategy, as they provide some level of protection against competitors, even if their solution may be better.

He illustrates the point with the widespread adoption of the QWERTY keyboard layout, even though it’s not the most efficient one.

“…many innovations fail because consumers irrationally overvalue the old while companies irrationally overvalue the new.”

Approaching the matter from the innovator’s side, if your product is too innovative in a sense that it requires the user to turn his life around to be able to use it, it’s not going to work. That’s what is usually referred to as “ahead of its time”, which may be true some of the time, but the real thing might be that while the product itself is very much needed in the marketplace, its design prevents it from being adopted. The key thing to remember is don’t expect your users to make a big change or investment just to try your product. So design a product that requires incremental changes.

Building the Mind Monopoly

“The fact is that successfully changing long-term user habits is exceptionally rare.”

“The enemy of forming new habits is past behaviors, and research suggests that old habits die hard. Even when we change our routines, neural pathways remain etched in our brains, ready to be reactivated when we lose focus.”

“Adapting to the differences in the Bing interface is what actually slows down regular Google users and makes Bing feel inferior, not the technology itself.”

Can a company ever become so confident as to advertise its direct competition (and make money off them)? Apparently that’s exactly what Amazon is doing when it shows you related products sold not by Amazon but individual sellers. The reason why Amazon can afford to do that is because it’s become the “go to” shopping place as well as:

“By addressing shoppers’ price concerns, Amazon earns loyalty even if it doesn’t make the sale and comes across as trustworthy in the process. The tactic is backed by a 2003 study, which demonstrated that consumers’ preference for an online retailer increases when they are offered competitive pricing information.”

Would this work for your business? Hard to say. But it’s also hard to deny that as a user, you appreciate the straightforwardness of a business that doesn’t want to sell to you by all means, and puts your interest before its own (by the looks of things at least). I’d be more likely to go back to such a place – we all are.

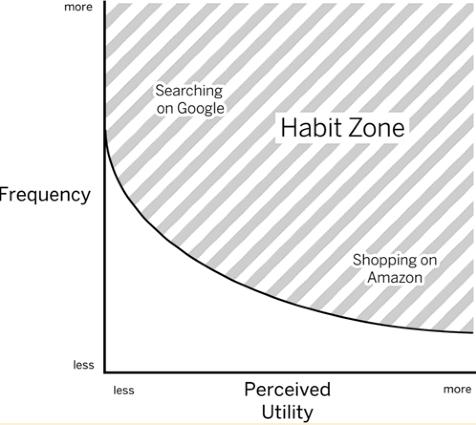

In the Habit Zone

“Googling occurs multiple times per day, but any particular search is negligibly better than rival services like Bing. Conversely, using Amazon may be a less frequent occurrence, but users receive great value knowing they’ll find whatever they need at the one and only “everything store.””

According to Eyal, actions that are done less frequently will never become habits in a sense that they always involve a conscious choice. I’d respectfully disagree with that. Once a website becomes the default choice for something, people tend to go back to the same place every time even if they only do it once a month. If you use IMDB to look up movies, the next time you want to find out about a new movie, you won’t have to decide whether to go to Rotten Tomatoes or IMDB.

Vitamins Versus Painkillers

“Painkillers solve an obvious need, relieving a specific pain, and often have quantifiable markets.”

“Vitamins, by contrast, do not necessarily solve an obvious pain point. Instead they appeal to users’ emotional rather than functional needs.”

“We feel satisfied that we are doing something good for our bodies— even if we can’t tell how much good it is actually doing us.”

“Habit-forming technologies are both. These services seem at first to be offering nice-to-have vitamins, but once the habit is established, they provide an ongoing pain remedy.”

This, and the inverse definition of habits, makes me think that we arrived at a point where moral question start to arise. There is a whole chapter dedicated to this aspect of the issue, but I must add right here that while according to Eyal “A habit is when not doing an action causes a bit of pain.”, taking it a step further, an addiction is when not doing an action causes a lot of pain.

Telling the difference between a bit and a lot of pain is where the slope gets slippery, because it’s impossible. A bit may be a lot to someone else or to the same person under different circumstances. Again, more on this in the appropriate chapter, but I don’t want to hide my suspicion that the potential dangers of habit forming products are underestimated in this book as well as by the general public.

2. Trigger

“I don’t have a problem or anything. I just use it whenever I see something cool. I feel I need to grab it before it’s gone.”

That’s a young woman with an “instagram habit”. (She would qualify as an addict to my mind, but let’s leave that aside for now.)

“External triggers are embedded with information, which tells the user what to do next.”

Next, Eyal explains different types of external triggers next, which are the first step in a process, which forms its own internal triggers so that external triggers become unnecessary.

External Triggers

1. Paid Triggers

“Advertising, search engine marketing, and other paid channels are commonly used to get users’ attention and prompt them to act. Paid triggers can be effective but costly ways to keep users coming back. Habit-forming companies tend not to rely on paid triggers for very long, if at all.”

2. Earned Triggers

“Earned triggers are free in that they cannot be bought directly, but they often require investment in the form of time spent on public and media relations.”

3. Relationship Triggers

“One person telling others about a product or service can be a highly effective external trigger for action.”

4. Owned Triggers

“Owned triggers consume a piece of real estate in the user’s environment. They consistently show up in daily life and it is ultimately up to the user to opt in to allowing these triggers to appear.”

While some industries can rely solely on external triggers, what gives habit forming companies an edge is they don’t need to.

Internal Triggers

“When a product becomes tightly coupled with a thought, an emotion, or a preexisting routine, it leverages an internal trigger.”

“Internal triggers manifest automatically in your mind. Connecting internal triggers with a product is the brass ring of consumer technology.”

The “beauty” of Internal triggers is that they happen all the time. They can be tiny emotional changes, and especially negative ones are powerful even if they are not strong enough to register. We’re not aware that we’re lonely, but just a spark of loneliness or feeling of missing out will make us check Facebook. Frustration, boredom, indecisiveness and confusion work much in the same way.

Although the Facebook and email checking seems alleviate our pain (or rather itch), they don’t.

“We identified several features of Internet usage that correlated with depression,” “For example, participants with depressive symptoms tended to engage in very high e-mail usage … Other characteristic features of depressive Internet behavior included increased amounts of video watching, gaming, and chatting.”

Going back to the process of internalizing the trigger: “The association between an internal trigger and your product, however, is not formed overnight. It can take weeks or months of frequent usage…”

The association may not form overnight, but it does form eventually. A recent study shows that Facebook is still way the most popular social network among US teenagers and that a staggering 28% said they use facebook all the time. If you also consider that almost half of its users check Facebook before getting out of bed, you get a good idea of the power of internal triggers.

And of the severity of the problem too. There are at least two hundred million people on the planet who compulsively check Facebook every ten minutes. And many more, who are hooked on other, similarly addictive products. While the focus of this book is not the consequences or side effects of habit forming products, but how to build them, I think one should not be mentioned without mentioning the other.

Building for Triggers

“The ultimate goal of a habit-forming product is to solve the user’s pain by creating an association so that the user identifies the company’s product or service as the source of relief.”

“First, the company must identify the particular frustration or pain point in emotional terms, rather than product features.”

“These common needs are timeless and universal. Yet talking to users to reveal these wants will likely prove ineffective because they themselves don’t know which emotions motivate them.”

That’s where the 5 whys method comes in, which is essentially asking the user why they use a product up to the point that they reveal a fundamental emotion, such as loneliness or fear, which usually happens within 5 rounds of questions.

“Like many social networking sites, Instagram also alleviates the increasingly recognizable pain point known as fear of missing out, or FOMO.”

3. Action

“To initiate action, doing must be easier than thinking. Remember, a habit is a behavior done with little or no conscious thought.”

Three ingredients are required to initiate any and all behaviors:

- Motivation

- Ability

- Trigger

Motivation

Motivation defines the level of desire to take action.

“Fogg states that all humans are motivated to seek pleasure and avoid pain; to seek hope and avoid fear; and finally, to seek social acceptance and avoid rejection”

Eyal cites some examples from advertising to illustrate the above and to explain how building on existing motivations can work in the designer’s favour.

Ability

“Ability is the capacity to do a particular behavior.”

“Any technology or product that significantly reduces the steps to complete a task will enjoy high adoption rates by the people it assists.”

“Take a human desire, preferably one that has been around for a really long time … Identify that desire and use modern technology to take out steps”

The author takes examples from the world if the internet and how the websites and technologies that have become popular, all simplified something. For instance Google was not the first search engine, but it had the most simplistic look. The infinite scroll popularized by Pinterest takes away the pain of turning pages and makes the experience flawless and so much more addictive. The point is: enabling the user to take action (when doing becomes easier than thinking) is a key factor of success.

On Heuristics and Perception

“There are many counterintuitive and surprising ways companies can boost users’ motivation or increase their ability by understanding heuristics—the mental shortcuts we take to make decisions and form opinions.”

Two different ways of perceiving the same thing may lead to very different outcomes about it. Next, we’ll see some practical examples for this.

The Scarcity Effect

In an experiment, one jar held ten cookies while the other contained just two.

“Although the cookies and jars were identical, participants valued the ones in the near-empty jar more highly. The appearance of scarcity affected their perception of value.”

“The study showed that a product can decrease in perceived value if it starts off as scarce and becomes abundant.”

The Framing Effect

“The mind takes shortcuts informed by our surroundings to make quick and sometimes erroneous judgments.”

When a world class violinist performed his concert in the subway station, few stopped to listen. But when framed in the context of a concert hall, tickets would sell out in a few days at extremely high prices.

When people were given samples of wine and told the price of each bottle, there was a real correlation between their liking and the price. Brain scanners showed the correlation was real, even though the price information was flawed. So people liked the wine more that they thought was more expensive.

The Anchoring Effect

“People often anchor to one piece of information when making a decision.”

If you see a product at 50% off, you may buy it even if it’s more expensive than the same product, which is not on sale.

The Endowed Progress Effect

“Two groups of customers were given punch cards awarding a free car wash once the cards were fully punched. One group was given a blank punch card with eight squares; the other was given a punch card with ten squares that came with two free punches. Both groups still had to purchase eight car washes to receive a free wash; however, the second group of customers — those that were given two free punches— had a staggering 82 percent higher completion rate.”

“The study demonstrates the endowed progress effect, a phenomenon that increases motivation as people believe they are nearing a goal.”

The same tactic is often employed by websites who’d like you to fill out a form or a survey. Just by showing a status bar and informing the user that the end is near, people are a lot more likely to complete such series of actions.

4. Variable Reward

“The test subjects played a gambling game while Knutson and his team looked at which areas of their brains became more active. The startling results showed that the nucleus accumbens was not activating when the reward (in this case a monetary payout) was received, but rather in anticipation of it.”

“The study revealed that what draws us to act is not the sensation we receive from the reward itself, but the need to alleviate the craving for that reward.”

“Novelty sparks our interest, makes us pay attention, and— like a baby encountering a friendly dog for the first time—we seem to love it.”

But not so much for the second and any subsequent times, unless it’s always a new kind of dog.

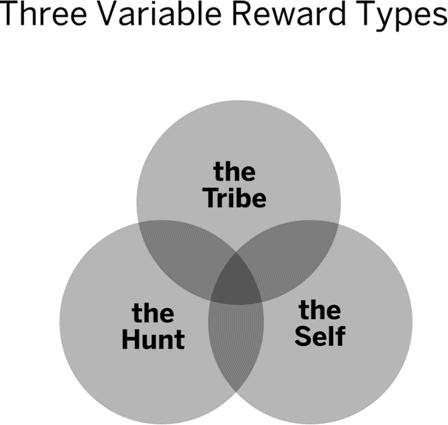

Rewards of the Tribe

“Our brains are adapted to seek rewards that make us feel accepted, attractive, important, and included.”

“…people who observe someone being rewarded for a particular behavior are more likely to alter their own beliefs and subsequent actions.”

“…this technique works particularly well when people observe the behavior of people most like themselves or who are slightly more experienced (and therefore, role models).”

Eyal illustrates the above by explaining how websites with user generated content work. Essentially, people put the work in because of the acknowledgement they get from the community. Once this reward is mixed with monetary rewards though, people stay away as the money they could get usually doesn’t match the effort they make and the non-monetary rewards are much more powerful (and also variable) in this sense. Dan Ariely comes to a similar conclusion in his book, Predictably Irrational, which I highly recommend to everyone reading this post.

Rewards of the Hunt

“The need to acquire physical objects, such as food and other supplies that aid our survival, is part of our brain’s operating system.”

The author mentions machine gambling, and hunting for good content on Twitter and Pinterest to illustrate the above.

Rewards of the Self

“…people desire, among other things, to gain a sense of competency. Adding an element of mystery to this goal makes the pursuit all the more exciting.”

As much as a sense of competence, it’s a sense of achievement: the feeling of “I’m getting things done”, “I’m making progress” is what lies at the heart of this in my opinion. Eyal ciets video games, email and codeacademy as examples.

“Only by understanding what truly matters to users can a company correctly match the right variable reward to their intended behavior.”

Eyal warns that variable rewards are not a one-size-fits-all solution and demonstrates the point with the story of Mahalo, a platform similar to Quora, which gained significant traction, but never made it to mainstream, mostly because of its flawed reward scheme that involved money.

Maintain a Sense of Autonomy

Eyal’s experience with the app MyFittnessPal reveals why it’s impossible to get people to make big changes. As Eyal says, the app required him to keep a food diary, which he never did before so after a few days it became a pain and it eventually made him abandon the app entirely.

On the other hand, another health app, Fittocracy, work much better for him, because he instantly got support from the community, which kept him motivated, and there was nothing he had to do.

“Companies that successfully change behaviors present users with an implicit choice between their old way of doing things and a new, more convenient way to fulfill existing needs.

Beware of Finite Variability

“Experiences with finite variability become less engaging because they eventually become predictable.”

The author mentions two examples here. The first is a TV show, Breaking Bad, which starts out as really interesting and groundbreaking in many ways, but people lost interest after a while. I can personally stand by this: I’ve recently watched the first 3 seasons, but I didn’t go any further. I felt like they kept chewing a bone that had no more meat on it.

The second example is that of Zynga, the company that created the insanely successful game, Farmville. And then they thought they could just apply the same logic in different fields so they made Citiville, Chefville etc, but people didn’t buy it anymore. It was the same thing, only wrapped in a different kind of paper.

5. Investment

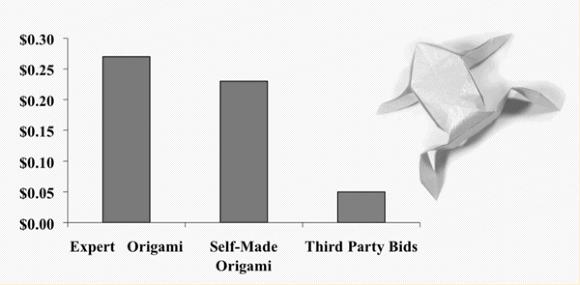

“The more users invest time and effort into a product or service, the more they value it. In fact, there is ample evidence to suggest that our labour leads to love.”

We Irrationally Value Our Efforts

According to a study, people valued the origami they made themselves way higher than those of similar quality, but made by others, and almost as high as professional quality.

This has become known (after Dan Ariely) as the IKEA effect. Anything we put our personal time and effort into, we value irrationally high.

We Seek to Be Consistent with Our Past Behaviors

“A team of researchers asked a group of suburban residents to place large, unsightly signs in front of their homes that read DRIVE CAREFULLY. Two groups were tested. In the first group only 17 percent of the subjects agreed to the request, while 76 percent of those in the second group agreed.”

The only difference between the two groups was that the second group had been asked previously to put a smaller sign up, which they did without much objection.

Once they agreed to the first request, the second seemed much less outrageous so they complied.

Point is: get your user to agree to something that is very easily agreeable before you want them to sign the real deal.

We Avoid Cognitive Dissonance

“Our bodies are designed to reject alcohol and capsaicin, the compound that creates the sensation of heat in spicy food. Our innate reaction to these acquired tastes is to reject them, yet we learn to like them through repeated exposure. We see others enjoying them, try a little more, and over time condition ourselves. To avoid the cognitive dissonance of not liking something that others seem to take so much pleasure in, we slowly change our perception of the thing we once did not enjoy.”

“Rationalization helps us give reasons for our behaviors, even when those reasons might have been designed by others.”

In other words, we do stuff for all sorts of reasons, most of which we are not even aware of, and once done, we manufacture reasons for having them done, to make ourselves feel good.

It’s good to remember that “…investments are about the anticipation of longer-term rewards, not immediate gratification.” and that “…in contrast to the action phase, the investment phase increases friction.”

While it’s very important to make the first action as easy as possible (otherwise people won’t’ take it), in the investment phase, more difficulty increases loyalty. Up to a certain point of course: if it’s too difficult, people will still quit.

It’s also important that “…asking users to do a bit of work comes after users have received variable rewards, not before.”

Storing Value

“The stored value users put into the product increases the likelihood they will use it again in the future and comes in a variety of forms.”

Data

“If we could get users to enter just a little information, they were much more likely to return.” – says one of LinkedIn’s product managers.

Followers

“Investing in following the right people increases the value of the product by displaying more relevant and interesting content in each user’s Twitter feed. It also tells Twitter a lot about its users, which in turn improves the service overall.”

Reputation

“Reputation is a form of stored value users can literally take to the bank.”

It’s like a new kind of online currency that can only be earned. Which is why “Reputation makes users, both buyers and sellers, more likely to stick with whichever service they have invested their efforts in to maintain a high-quality score.”

Skill

“Once users have invested the effort to acquire a skill, they are less likely to switch to a competing product.”

Who would want to learn to use different tool, which creates much the same end product works in a very different way. Just think Apple vs PC.

Loading the Next Trigger

“Users set future triggers during the investment phase, providing companies with an opportunity to reengage the user.”

The author goes on by describing examples for the above including any.do, Tinder, Snapchat and Pinterest (as well as mentioning Photoshop previously).

6. What Are You Going to Do with This?

So this is the chapter dealing with the morality of creating new habits and getting users hooked on a product.

“Creating habits can be a force for good, but it can also be used for nefarious purposes. What responsibility do product makers have when creating user habits?”

In the preparation of the topic, Eyal quotes “Ian Bogost, the famed game creator and professor”, who called habit forming products the “cigarette of this century”.

Then he softens that statement by referring to Weight Watchers, which is unquestionably and deliberately a habit forming product with an obviously acceptable purpose and no moral issues attached.

He continues: “Ubiquitous access to the web, transferring greater amounts of personal data at faster speeds than ever before, has created a more potentially addictive world. According to famed Silicon Valley investor Paul Graham, we haven’t had time to develop societal “antibodies to addictive new things.” Graham places responsibility on the user: “Unless we want to be canaries in the coal mine of each new addiction— the people whose sad example becomes a lesson to future generations— we’ll have to figure out for ourselves what to avoid and how.””

Still quoting other people:

“Chris Nodder, author of the book Evil by Design, writes, “It’s OK to deceive people if it’s in their best interest, or if they’ve given implicit consent to be deceived as part of a persuasive strategy.”

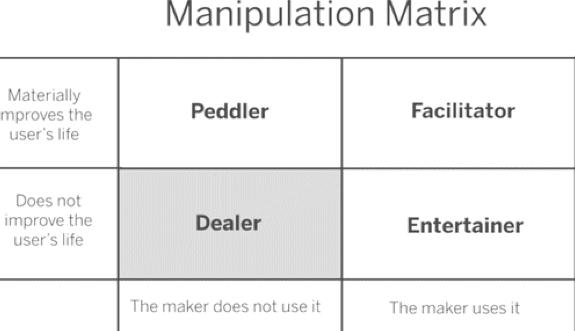

The author’s own contribution to the debate comes in the form of the Manipulation Matrix.

Facilitators create awesome products that they use themselves and that clearly make the world a better place.

On the opposite end of the scale, dealers create product that they would never use because they are aware of its harmful effects.

Peddlers and entertainers are somewhere in between.

While this matrix can be a useful tool if you’re having doubts about your own product (if you want to sell doughnuts for instance), it doesn’t offer any guidance with regard to the millions of people whose lives are falling apart, because they’ve developed an addiction to products created by perhaps well meaning (but profit oriented) Facilitators or Entertainers.

“Industry estimates for pathological users of even the most habit-forming technologies, such as slot-machine gambling, are just 1 percent.”

“Even though the world is becoming a potentially more addictive place, most people have the ability to self-regulate their behaviors.”

This is where I believe the author is wrong. Pathological users or abusers of slot machines and substances may be a tiny proportion of the population, and similarly, perhaps no more than 1% of people form so strong addictions to modern technologies that it would threaten their lives. However, there are masses of people (according to this study 28% of Facebook users) who I’d refer to as latent addicts. They know, they are on Facebook all the time, but they don’t know how it affects all other aspects of their lives.

And that’s exactly the danger of habit forming products made available to the masses: they turn people into addicts, but unlike substance addicts, these users and even the people around them don’t know they have a problem.

Perhaps Eyal is right and people will figure out how these products work eventually and come up with a smart response at a social or individual level. The difference with these new technologies though, as compared to a sugar or tobacco addiction for instance, is that they rewire our brains. What used to be engaging is now boring. Anything longer than 140 characters is becoming a drag. Nicholas Carr’s book, The Shallows, will shed more light on this.

At the same time, too much of any good thing will have undesired effects, so Eyal is right in suggesting that the end user has the power of choice. I’d only urge creators of habit forming products to make the risks of overusing and abusing their products as clear as they make terms of use so that more users can make better choices even if that’s against the motive of maximizing profits.

7. Case Study: The Bible App

This case study introduces the Bible App of YouVersion works. If you haven’t heard of it before, it’s quite a revelation…

Long story short, the app sends pieces of the Bible to the user to read. The way it hooks people is the content is broken into digestible pieces, and there is only so much reading every day that it doesn’t overwhelm the user, but leaves them wanting to come back for more.

The reading plan provides a steady schedule and is built in a way that the easiest pieces come first so that users are not deterred by complex textures initially. The plans are also customizable in a way, there are 400 different plans to suit every need.

The key is apparently daily reading, which is initially triggered by the notification of the app, but later becomes a habit.

Some priests have also adopted the abb and use it in sermons instead of turning pages in bulky books, which accelerate the spread.

Key points as summarized by the author:

- The Bible App was far less engaging as a desktop Web site; the mobile interface increased accessibility and usage by providing frequent triggers.

- By separating the verses into small chunks, users find the Bible easier to read on a daily basis; not knowing what the next verse will be adds a variable reward.

- Every annotation, bookmark, and highlight stores data (and value) in the app, further committing users.

8. Habit Testing and Where to Look for Habit-Forming Opportunities

In this finak chapter, Eyal provides some practical guidance for building habit forming products and makes some valid points about the future of technology.

“The Hook Model can be a helpful tool for filtering out bad ideas with low habit potential as well as a framework for identifying room for improvement in existing products.”

“When technologies are new, people are often skeptical. Old habits die hard and few people have the foresight to see how new innovations will eventually change their routines. However, by looking to early adopters who have already developed nascent behaviors, entrepreneurs and designers can identify niche use cases, which can be taken mainstream.”

“Wherever new technologies suddenly make a behavior easier, new possibilities are born.”

“A profusion of interface changes are just a few years away. Wearable technologies like Google Glass, the Oculus Rift virtual reality goggles, and the Pebble smartwatch promise to change how users interact with the real and digital worlds.”

Key Takeawys of the Book

- Companies that leverage the power of habit forming products have a massive advantage over those who don’t.

- The hook cycle is built of four major steps

- Trigger

- Action

- Variable Reward

- Investment

- External triggers are needed to form habits, but these become internal in the process and are not needed later.

- Three things are needed for action

- Trigger

- Motivation

- Ability

The designer must make sure to enable the user to take action by making it easier than thinking about.

- The reward must have a variable element to it in order to keep the user coming back for more

- The hook cycle is completed, a new habit is formed once the user made a significant investment in the products that will make its use easy to rationalize.

- While the user always has the power to quit, a significant number of people develop unhealthy addictions to habit forming products.

- A habit is really adopted when it occurs daily.

- What we’ve seen is only the beginning. New technologies open up huge space for new habit forming products.

Leave a Reply